Use this tool to solve common problems you'll find in your gospel classroom. Select from the options below to find teaching techniques that will help you solve some of the most common problems in LDS gospel classrooms:

To help class members share how learning during class is blessing their lives, you could write the following question on the board: What is something you did because of what you read in the scriptures this week?

To help class members share what they are learning, you might ask them to write questions, comments, or insights from their reading on strips of paper and put them into a container. Draw strips from the container to discuss as a class.

by Salena Thomas

We played Stump the Teacher. I used this with Luke 1 where the kids were mostly familiar with the stories.

So their goal was to ask me questions that I couldn't answer. If they stumped me then they got a small piece of candy. As I answered or didn't answer the questions I was able to elaborate on details and give a little more insight into the story. They couldn't keep out of the scriptures. Then I wrapped up with the principle I wanted them to take from it.

I had them use their scriptures to find questions. Sometimes they didn't ask a correct question because they only read the one verse. So I had to ask for clarification which meant they had to go back and read more to get the right question. It was great. I did not use the scriptures to answer the questions. I loved it when they stumped me because they would give me the correct answer. - They learned it themselves. And then I was able to elaborate as we went. For example, I knew they'd probably ask about the course of Zacharias. So I on purpose did not try to remember the correct course but I got all the background info on what a course was. So they stumped me and I was able to give them a lot more information.

Maureen Fepuleai: Our class ended up splitting themselves into boys and girls teams and tried to stump one another lol. Everybody got involved - got quite competitive! The girls team won by a big margin and what made it all the more beautiful, is that all of the students decided to combine their chocolate prizes and divide it into equal shares for everybody so that nobody missed out. It was so heartwarming for me to see them put their learning in action!

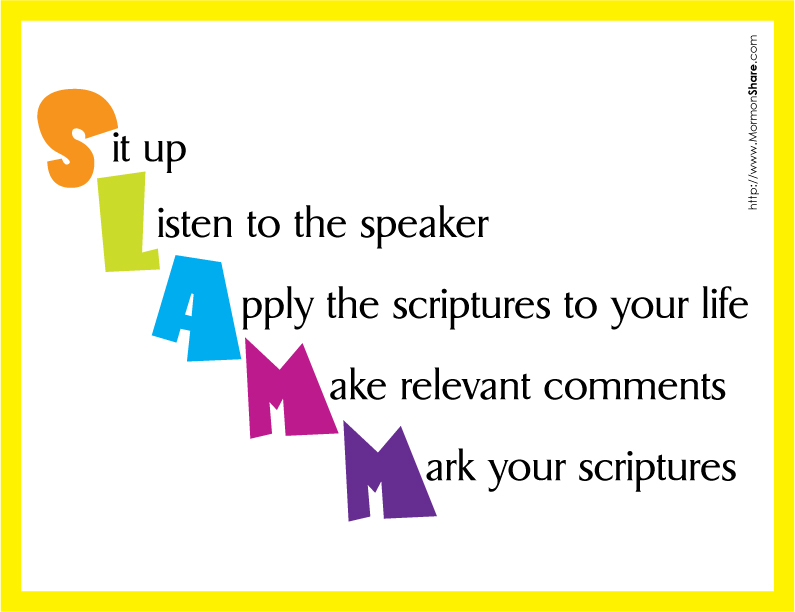

I used this acronym as my "classroom rules" for Seminary. They are Thou Shalts, instead of Thou Shalt Nots. I find this creates a positive atmosphere in the classroom, where I'm asking them to behave a certain way as opposed to constantly telling students to stop, stop, stop.

SLAMM Stands for

During class, if someone is talking over someone else, I might say, "Adam, are you SLAMMing Jake?" to help them focus. If someone is slumping down in the couches, I remind the class to SLAMM. It's a fast way to remind everyone what the rules are and to stay engaged.

I probably would not use classroom rules with a group of adults, but you can use SLAMM with youth and children very effectively.

There are questions you don’t know the answer to, and for which you know no answer has been revealed. One of the most powerful skills a teacher can develop is the self-control is to say, ‘I don’t know’, and STOP.

It takes a lot of self-control to achieve this top-level teaching skill. Most teachers have never seen it demonstrated, and many may think they’re already doing it. Here’s a typical response to a difficult question in a Seminary or Institute class:

Student: Will women ever get the priesthood?

Teacher: I don’t know, but they could. Women haven’t been ordained to the priesthood, but they act with the authority of priesthood when they officiate in temple ordinances. They can also act with priesthood power in their callings. Women can be presidents of organizations although they can’t have priesthood keys. They serve on ward councils and help with most church leadership. Women are essential to the organization of the church. Plus, women don’t need the priesthood because they already have motherhood. I don’t know why anyone wants priesthood anyway.

Tell me, did you notice the teacher’s “I don’t know”, or were you distracted by the rest?

Consider this response, which I think is better.

Student: Will women ever get the priesthood?

Teacher: I don’t know.

Student: Why not? Why can’t anyone answer this?

Teacher: I know this is an unsatisfying response, and if I had the answer you know I’d give it to you. Unfortunately, I really just don’t know the answer. I have a guess, but it would be just guessing and could still be wrong. I wish I could do better, but the best, most honest answer I can give you is I don’t know.

At this point you may need to help students understand why some questions can’t be answered. The question may call for speculation (Do spirits still possess bodies?) or information that hasn’t been revealed (Why don’t we know more about Heavenly Mother?). Reassure the student that you would give the student the answer if you could, but in your role as a Seminary teacher you can not speculate.

When someone asks questions, you may be tempted provide the plausible explanation someone else shared with you. If you aren’t sure about the answer, say so, and stop talking! It is definitely okay to invite a student to look up information with you and come back to share what they learn. It’s definitely okay to offer to look up ideas or pass along books you have with information for further study. It’s always okay to say you aren’t sure if there’s official information and promise to look it up (as long as you keep your promise).

Don’t speculate while teaching, even if you say clearly that you are speculating. Students will hear the speculation more than the I don’t know, and it may eventually cause a loss of faith. From the GTLH, p 51 “[R]esources should not be used to speculate, sensationalize, or teach ideas that have not been clearly established by the Church. Even if something has been verified or published before, it still may not be appropriate for use in the classroom. Lessons should build students’ faith and testimony.”

It is essential that you resist the temptation speculate. Learn to say ‘I don’t know’, and stop.

Teaching students to use the Gospel Library to answer questions is one of my very favorite teaching techniques. In my opinion taking the time to teach students how to look up and answer when you can easily answer it yourself, separates good teachers from excellent ones.

Using this method will take more time in class, and you need to be very proficient at your use of the Gospel Library in order to not frustrate students with your own inability to use the tools. You must know what type of information is found in the Bible Dictionary and Gospel Topics Essays and Church History essays, and you will need to be ready to go in an instant. However, I think withholding an answer slightly while you teach students how to find the answer is one of the most valuable things a teacher can do. Remember the old saying: “Give a man a fish and he eats for a day; teach a man to fish and he eats for a lifetime?” For Seminary it might be: “Give a student an answer and they have ten minutes of peace; teach a student how to fish for answers, and they can feast on the words of eternal life forever.”

When I taught Seminary, I plugged my computer into the television every day because we used the online music tool to provide our hymns. If a question came up, I could Google the answer or look it up at LDS.org right in front of the class. We had discussions about how to determine between good and bad sources, and especially how to use the tools in the Gospel Library to answer questions. Plan ahead to be ready to **demonstrate how** to answer a question. As you get to know your students, you will be able to predict the questions that will come up during class and can prepare to respond. Here’s an example of how our class learned to use the Bible Dictionary during our study of the Old Testament:

When we read about giants in the Old Testament, I knew my students would have the typical questions: “Is this for real? Were they really giants or were people just smaller? Is this a mistranslation? How big were these giants really?” I looked up Giants in the Bible Dictionary and read a good bit about Giants online before class, so I knew where to look for answers. When students began questioning, I let them discuss it for a minute or two until it became clear they were all engaged, and they all knew no one actually knew the answers. I asked, “Hey, would you like to take a minute from class to figure this giant-thing out?” “YES!” “Well, how do you think we could find out about giants……” “Bible Dictionary!”

We all turned to the Bible Dictionary together and read all the footnotes and cross-references about Giants. The lesson was one of the most important things we did all year. From then on, students began turning to the Bible Dictionary first when they had a question -- instead of me! They had learned to fish.

In the case of the giants, the “difficult” question was not as serious as a question as polygamy or race and the priesthood, but it was a question that was both interesting and easily answered using the tools available. Students used the Gospel Library tools in a real life situation in the classroom, and then could apply that skill to their own personal study. Look for ways to teach students to use tools and revelations to find their own answers. Help them learn to fish.

Most of us talk too much when we answer a question. It is our natural reaction to share all the information we have on a subject before finding out what the student already knows or how anxious he or she is to know it. In order to answer briefly, you should first ensure you understand what’s really being asked, and the urgency with which the question is being asked. This will require you to slow down and gather more information before you respond.

Consider the first time a child asked you “Where do babies come from?” The answer you gave was dictated by how long the child had been wondering about the question, the maturity of the child, and the “real” question. If the question just occurred to the child while watching a television show that showed a new baby, your response was different than if the child had been pondering the origins of man for a while. The same applies to Seminary. When you’re asked a question, you might say, “That’s a really thoughtful question. Have you been thinking about that for a while?” or “That’s a complicated question. I love it! Please explain to me what you’re thinking is so I give you my best answer.”

Please take the time to drill down and collect the information you need to answer questions briefly and simply. Showing students you want to first understand them and then answer will build trust and show you love them. Complicated answers confuse students and may try faith. Simple answers help students understand your response and usually build faith.

Christy Elliott Vogel:

Here is another idea NY coordinator suggested: write the series of questions on the board (search through apply and testify) and ask them to answer one of them in their journals, then share. Those who are more intimidated will pick less personal questions, but at least they will share something.

Throughout the Seminary year -- but especially as you approach the end of the year -- you may wish to look for ways to introduce (for younger students) or reinforce (for graduating seniors) all Seminary Doctrinal Mastery (DM) scriptures.

Here are a few possible ideas to help you do so:

By Becky Edwards

www.edutopia.org/blog/alternatives-to-round-robin-reading-todd-finley

1. Choral Reading

The teacher and class read a passage aloud together, minimizing struggling readers' public exposure. In a 2011 study of over a hundred sixth graders (PDF, 232KB), David Paige found that 16 minutes of whole-class choral reading per week enhanced decoding and fluency. In another version, every time the instructor omits a word during her oral reading, students say the word all together.

2. Partner Reading

Two-person student teams alternate reading aloud, switching each time there is a new paragraph. Or they can read each section at the same time.

3. PALS

The Peer-Assisted Learning Strategies (PALS) exercises pair strong and weak readers who take turns reading, re-reading, and retelling.

4. Silent Reading

For added scaffolding, frontload silent individual reading with vocabulary instruction, a plot overview, an anticipation guide, or KWL+ activity.

5. Teacher Read Aloud

This activity, says Julie Adams of Adams Educational Consulting, is "perhaps one of the most effective methods for improving student fluency and comprehension, as the teacher is the expert in reading the text and models how a skilled reader reads using appropriate pacing and prosody (inflection)." Playing an audiobookachieves similar results.

6. Echo Reading

Students "echo" back what the teacher reads, mimicking her pacing and inflections.

7. Shared Reading/Modeling

By reading aloud while students follow along in their own books, the instructor models fluency, pausing occasionally to demonstrate comprehension strategies. (PDF, 551KB)

8. The Crazy Professor Reading Game

Chris Biffle's Crazy Professor Reading Game video (start watching at 1:49) is more entertaining than home movies of Blue Ivy. To bring the text to life, students . . .

9. Buddy Reading

Kids practice orally reading a text in preparation for reading to an assigned buddy in an earlier grade.

10. Timed Repeat Readings

This activity can aid fluency, according to literacy professors Katherine Hilden and Jennifer Jones (PDF, 271KB). After an instructor reads (with expression) a short text selection appropriate to students' reading level (90-95 percent accuracy), learners read the passage silently, then again loudly, quickly, and dynamically. Another kid graphs the times and errors so that children can track their growth.

11. FORI

With Fluency-Oriented Reading Instruction (FORI), primary students read the same section of a text many times over the course of a week (PDF, 54KB). Here are the steps: